Source: https://www.thoughtco.com/very-short-history-of-cote-divoire-43647

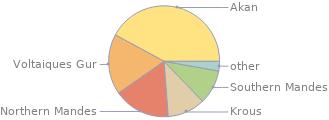

Our knowledge of the early history of the region now known as Côte d’Ivoire is limited—there is some evidence of Neolithic activity, but mush still needs to be done in investigating this. Oral histories give rough indications of when various peoples first arrived, such as the Mandinka (Dyuola) people migrating from the Niger basin to the coast during the 1300s.

In the early 1600s, Portuguese explorers were the first Europeans to reach the coast. They initiated trade in gold, ivory, and pepper. The first French contact came in 1637—along with the first missionaries.

In the 1750s the region was invaded by Akan peoples fleeing the Asante Empire (now Ghana). The established the Baoulé kingdom around the town of Sakasso.

A French Colony. French trading posts were established from 1830 onwards, along with a protectorate negotiated by the French Admiral Bouët-Willaumez. By the end of the 1800s, the borders for the French colony of Côte d’Ivoire had been agreed with Liberia and the Gold Coast (Ghana).

In 1904 Côte d’Ivoire became part of the Federation of French West Africa (Afrique Occidentale Française) and run as an overseas territory by the Third Republic. The region transferred from Vichy to Free French control in 1943, under the command of Charles de Gaulle. Around the same time, the first indigenous political group was formed: Félix Houphouët-Boigny’s Syndicat Agricole Africain (SAA, African Agricultural Syndicate), which represented African farmers and landowners.

Independence. With independence in sight, Houphouët-Boigny formed the Parti Démocratique de la Côte d’Ivoire (PDCI, Democratic Party of Côte d’Ivoire)—Côte d’Ivoire’s first political party. On 7 August 1960, Côte d’Ivoire gained independence and Houphouët-Boigny became its first president.

Houphouët-Boigny ruled Côte d’Ivoire for 33 years, was a respected African statesman, and on his death was Africa’s longest-serving president. During his presidency, there were at least three attempted coups, and resentment grew against his one-party rule. In 1990 a new constitution was introduced enabling opposition parties to contest a general election—Houphouët-Boigny still won the elections with a significant lead. In the last couple of years, with his health failing, backroom negotiations attempted to find someone who would be able to take over Houphouët-Boigny’s legacy and Henri Konan Bédié was selected. Houphouët-Boigny died on 7 December 1993.

Côte d’Ivoire after Houphouët-Boigny was in dire straits. Hit hard by a failing economy based on cash crops (especially coffee and cocoa) and raw minerals, and with increasing allegations of governmental corruption, the country was in decline. Despite close ties to the west, President Bédié was having difficulties and was only able to maintain his position by banning opposition parties from a general election. In 1999 Bédié was overthrown by a military coup.

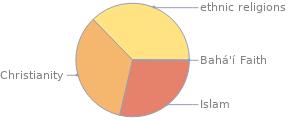

A government of national unity was formed by General Robert Guéi, and in October 2000 Laurent Gbagbo, for the Front Populaire Ivoirien (FPI or Ivorian Popular Front), was elected president. Gbagbo was the only opposition to Guéi since Alassane Ouattara was barred from the election. In 2002 a military mutiny in Abidjan split the country politically—the Muslim north from the Christian and animist south. Peacekeeping talks brought the fighting to an end, but the country remains divided. President Gbagbo has managed to avoid holding new presidential elections, for various reasons, since 2005.1